The CNDC published its technical report containing the results of market studies carried out on the conditions of competition in the pharmaceutical industry, especially, regarding the chain of distribution of drugs and the vertical and/or corporate integration between laboratories and distributors.

I. Introduction

The Comisión Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia (National Commission for the Defense of Competition, or the CNDC, for its Spanish acronym) published on December 23rd, 2019, a technical report that summarizes the results of a series of market studies carried out since 2017 on the conditions of competition in the pharmaceutical industry, with the aim to know the conditions of competition, especially, regarding the chain of distribution of drugs and the vertical and/or corporate integration between laboratories and pharmaceutical distributors and/or drug wholesalers.

For these purposes, information was required and hearings were held with different agents in the sector (laboratories, drug wholesalers, pharmaceutical distributors, public bodies, experts, etc.).

The same report describes the relevant aspects of the pharmaceutical market in Argentina from the point of view of Argentine Competition Law No. 27,442 (LDC), focusing particularly on the wholesale stage of distribution. An analysis of sales to the institutional channel is not included in the work, which represents approximately 24% of total sales.

The report has as background a complaint filed in the middle of 2012 by Farmacity against different actors in the pharmaceutical market (including centrally to laboratories and their three business chambers), and a penalty imposed at the request of the Antitrust Authority against a series of entities that bring together all the pharmacies in the province of Tucumán for the realization of a collusive horizontal practice.

This is a description of the status of the situation, which concludes CNDC’s investigation, and which does not raise behaviors to be investigated and/or recommended actions, notwithstanding that the CNDC itself states that it is expected that the pharmaceutical industry be at the center of the agenda of the competition enforcement authority.

Previously, at the beginning of 2014, the CNDC had initiated various ex officio investigations of markets that were considered as relevant (including medicine drugs for human consumption). This, concomitantly with the price controls carried out then by the Secretary of Commerce and the Price Information Regimes established by Resolution No. 29/2014 and regulated by Provision 6/2014 of the Secretary of Commerce of the Ministry of Economy and Public Finance, and according to the then applicable Information Regime of Joint Resolution No. 66/2014 and No. 3629/2014 of the Secretary of Commerce and the Federal Administration of Public Revenue (Argentine Tax Authority, AFIP), respectively. The number assigned to this file (C. 1486) corresponds to a conduct investigation, within which we have not been aware of any complaint or record that the file has been closed.

The following is a summary of the most relevant points of CNDC’s report, on which we are fully available to expand specifically if deemed convenient.

II. The value chain in the pharmaceutical industry in Argentina

The value chain of the pharmaceutical industry comprises the stages of: (i) research and development, (ii) commercial production; (iii) wholesale distribution; and (iv) retail marketing.

II.I. Research and development (R&D)

Research consists in the recognition of new molecules associated with properties of regulation of biological processes that allow the treatment of certain disease or pathology. The research phase concludes with toxicological studies and pharmacokinetic analysis. Upon completion of the investigation, the development of the drug requires a series of pre-clinical and clinical studies and then to be approved by the corresponding health authority.

R&D is a strongly regulated activity in terms of the possibility of commercial launch and dependent on the rate of innovations. There is a relatively small group of multinational capital laboratories that sell medicines in the country, which carry out R&D under the protection of a patent. These laboratories usually carry out intense marketing activities in order to position their products. On the other hand, there are local companies that produce medicines with expired patents.

The innovation activities of national laboratories are primarily aimed at the manufacture of new products based on known drugs and with expired patents. In the country there are 18 companies with national capital that elaborate and/or commercialize biotechnological medicinal specialties.

II.II Commercial production

Around 350 laboratories operate in Argentina. The majority are national companies with industrial plants based in the country, which have a greater presence in outpatient medications. Foreign laboratories lead the high-cost drug segment. There are also 40 state laboratories, with an estimated low market share.

The Argentine laboratories are grouped into four chambers: CAEMe (mostly multinationals), CILFA (medium and large Argentine labs), COOPERALA (smaller Argentine labs) and CAPGEN (small generic producers).

Without counting high-cost medicines, the 20 most important laboratories in the country account for 70% of total sales. None of them have a share of more than 10%. Although the industry concentration level appears to be low, the analysis of the whole pharmaceutical market requires disaggregation up to levels 3 or 4 (therapeutic class) of the ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Classification).

Nearly half of the relevant markets are highly concentrated. Regarding high-cost medicines, a high concentration of supply is recorded in a small number of pathologies and drugs. For most active ingredients, there is only one offering laboratory.

The main laboratories participate indirectly in the subsequent stages of the chain (wholesale distribution and commercialization), through corporate links with pharmaceutical distributors, drug wholesalers and mandatary or managing companies.

II.III Distribution

Pharmaceutical distributors and drug wholesalers are involved in this stage. In Argentina, the “buy-sell” and “delivery by logistics operator” (fee for service) systems coexist in addition. Medical visitors and pharmaceutical visitors, also participate.

Pharmaceutical distributors emerged in the 1990s as a result of a strategy of larger laboratories aimed at reducing distribution costs and inventories. 81% of the turnover of drugs sold in pharmacies is concentrated in 4 pharmaceutical distributors, which have as main shareholders national and foreign laboratories and have about 100 laboratories as clients (30% of the total).

Each laboratory uses a single distributor, but not a single drug wholesaler. It is the laboratory that chooses the distributor with which it operates, while the pharmacies are the ones that choose the drug wholesaler with which they operate. At an international level, the growing trend is the direct sales modality from laboratories to pharmacies, as well as models of reduced wholesale intermediation.

Drug wholesalers have a wide retail reach and play a very important role in areas with large numbers of stores or located in dispersed geographical spaces, with low population density. There are integral drug wholesalers and specialized drug wholesalers (they distribute exclusively high-cost medicines, grouped in CADDE). The integrals are grouped in ADEM, while the three largest together represent 60% of the turnover of integral drug wholesalers. Most laboratories do not have participation in large integral drug wholesalers. The specialized drug wholesalers do not have links with the laboratories.

II.IV Retail Marketing

There are about 12,700 pharmacies throughout the country, which are supplied byore than one drug wholesaler. There are also two types of pharmacies: single or family, and branches or franchises. During the last decade, there has been a great growth of networks or chains of pharmacies.

II.V Mandatary companies

Mandatary or managing companies are entities in charge of administering and auditing contracts or agreements for outpatient medicine and non-ambulatory drug benefits between laboratories and public healthcare service organizations, prepaid healthcare companies, hospitals and other agencies linked to the health system. The most important are Farmalink and Preserfar.

PAMI eliminated the intermediation of Farmalink. Since November 1, 2018, this activity is carried out by PAMI itself through the FARMAPAMI system. In March 2018, a joint purchase was made between several institutions that allowed the price reduction (high-cost medicines).

III. Prices

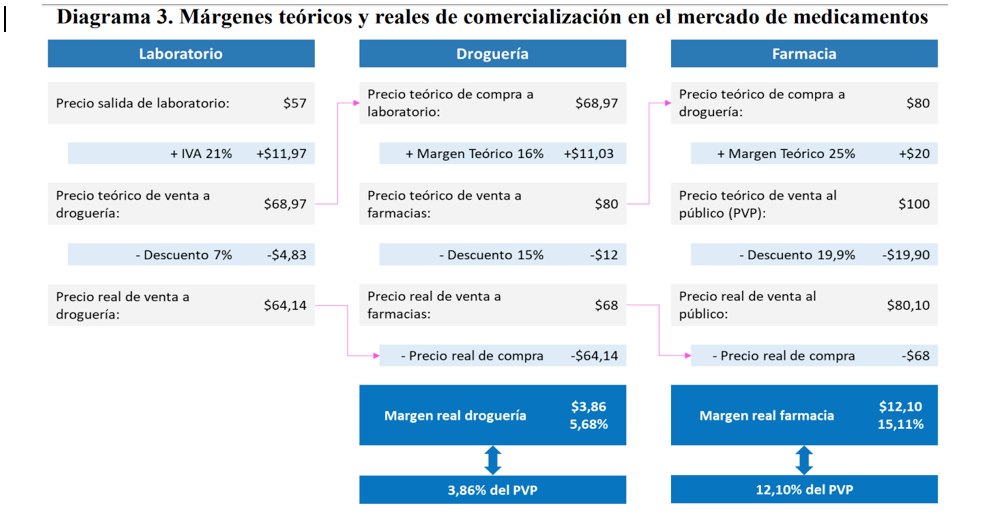

It is argued that the laboratories are the ones who set the prices along the chain, including the retail price (PVP). In the case of high-cost medicines, the participation of laboratories in price formation is more direct. The configuration of the price and margin system can have consequences that distort competition.

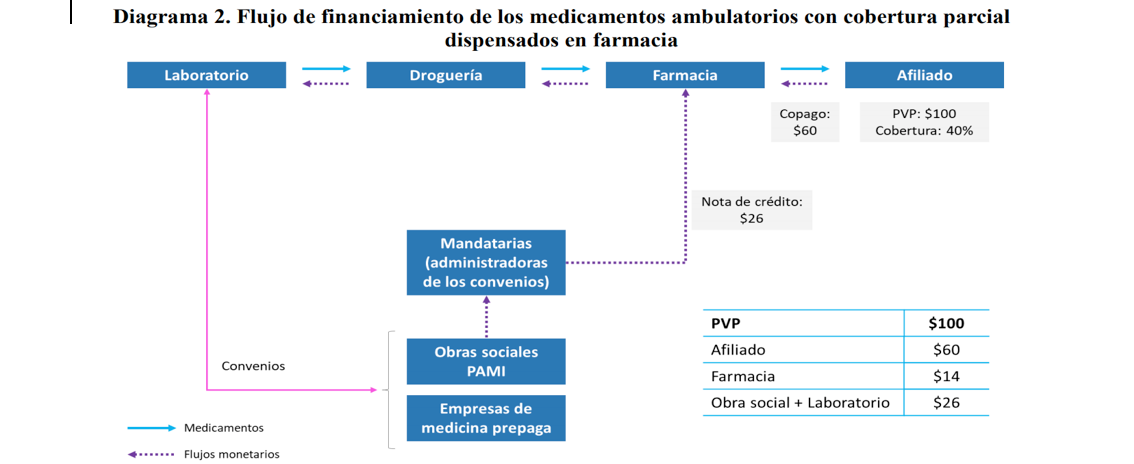

The operation of the settlement system of the agreements by the agents for outpatient medicines works, in broad strokes, as follows: The discount on drugs that the patient receives from part of the public healthcare service organization or prepaid healthcare companies (generally, 40% of the PVP, although in some cases, such as in the case of chronic diseases, it may be higher), health insurance covers between 10% and 15% of the PVP (according to the agreement with the manufacturing laboratory) and the rest is absorbed between the laboratory and the pharmacy. The agents are responsible for liquidating the discount of public healthcare service organizations and prepaid healthcare companies. The process begins when the patient acquires the medication and receives the corresponding discount. Then the pharmacist sends the die with the prescription and the patient’s signature to the agent, which validates the prescription and issues a credit note for the percentage of the discount that corresponds to the public healthcare service organizations or prepaid healthcare companies and to the laboratory, so that they can validate it. The pharmacist uses the credit note (with payment terms of up to 60 days) to cancel debt with the drug wholesaler. The latter uses the credit note to cancel debt with the laboratory. The laboratory accepts the credit note as a form of payment and then receives part of the discount applied by the public healthcare service organizations and prepaid healthcare companies. Diagram 2 illustrates this process.

Source: CNDC’s Report

Source: CNDC’s Report

IV. Synthesis and conclusions

The analysis of all the information collected by the CNDC in the framework of the refered investigation allowed the Authority to arrive at a series of considerations:

- In the first place, the emergence of pharmaceutical distributors has its origin in saving logistics costs for laboratories. At an international level, there is a growing trend towards this type of commercialization whereby wholesale marketing is carried out through agents that act on consignment, charging only for logistics, without having ownership of the inventory. In Argentina, pharmaceutical distributors have not replaced drug wholesalers, but have joined as another link in the chain. The activity of the pharmaceutical distributors, as providers of logistics services, presents high barriers to entry because it is an activity with strong economies of scale and the need to make high investments to meet the standards that are required to participate in the market. Given these characteristics, at that stage a small number of firms that distribute the entire portfolio of drugs operate: outpatient medicine, non-ambulatory and high cost. Most laboratories would not be significantly unable to switch between pharmaceutical distributors or sell directly to drug wholesalers, without resorting to the services of pharmaceutical distributors. The capital stock of each of the four largest pharmaceutical distributors, is owned (directly or indirectly) by the largest laboratories. The sum of the shares of these laboratories in the total industry is 37.7%. Therefore, these pharmaceutical distributors mostly distribute unrelated third party medications. Shareholdings may give laboratories access to competition information that is not otherwise available in the market, which could facilitate anticompetitive practices. However, pharmaceutical distributors have stated that there are high standards of confidentiality of the information in each laboratory, and these standards are reflected in the pharmaceutical distributors’ contracts with their customers. In fact, laboratories distribute only through a distributor.

- Secondly, within the framework of the investigation it has been observed that there are two very different types of drug wholesalers: the integral and the specialized ones. Integral drug wholesalers market the vast majority of medicinal specialties and laboratories in the market. Specialized drug wholesalers exclusively distribute high-cost medications. The market of integral drug wholesalers is concentrated in three drug wholesalers that together represent around 60% of the total turnover of the segment of integral drug wholesalers: Droguería del Sud, Droguería Monroe Americana and Droguería Suizo Argentina. The presence of shareholder laboratories (directly or indirectly) is lower in drug wholesalers than in the case of pharmaceutical distributors. In relation to the specialized drug wholesalers that distribute high-cost medicines, there would be no corporate participation of any laboratory. It has been observed that, in general, pharmacies stock up on more than one drug wholesaler for their daily business. The large integral drug wholesalers coexist with others of smaller size and regional presence, some with relevant participation in the areas where they distribute. Among the latter, the presence of cooperatives stands out, which in many cases are made up of pharmacies or pharmacy chains and appear to be a way of aggregating the demand of pharmacies.

- Third, it has been observed that although laboratories do not have significant corporate interests in drug wholesalers and no participation in pharmacies, they have the ability to set the retail price (PVP) of medicines, which seems to be the result of the agreements for dispensing medications with the different social security entities, which in general include the conditions under which the distribution and dispensing of the drugs included in the agreements is made. In their operation, these agreements include a mechanism to reimburse pharmacies through credit notes that, in fact, reduce their purchase alternatives and may produce some loyalty of pharmacies in relation to certain products. For all the preceding factors, it is concluded that the possibility that drug wholesalers or pharmacies may offer lower prices than those established by laboratories or generic drugs is very small. In the case of substitution for generic drugs, bioequivalence studies are particularly relevant in the cases in which they proceed.

Finally, the CNDC concludes by holding: “Given the particular conditions of competition in which the pharmaceutical industry operates in Argentina and the importance from the sanitary point of view that the population may have due access to the necessary medicines, and following the practice of competition authorities in countries with more extensive experience, it is expected that the pharmaceutical industry will continue to be at the center of the agenda of the competition enforcement authority”.

In our opinion, this report is the starting point to describe and analyze the reality of the production, distribution and marketing of medicines in Argentina, identifying the different actors -some of which are arranged or required by regulation and others have been created due to the local dynamics, like intermediaries and agents- but it does not advance, however, in the analysis of the effects or conditions that this structure has generated.

In this sense, the system implemented in fact, consciously or not, seems to allow vertical concentration, generating a favorable context for the exchange of sensitive information. At the same time, the sales power seems to be concentrated from top to bottom, using unregulated intermediaries (pharmaceutical distributors and agents), while pharmacies would remain atomized. We note that this report has not referred to the concentration that seems to be also happening between medical insurance entities and health centers.

The work also does not advance on the analysis of certain observed practices; for example: price publicity, pricing system and margins; system of reimbursements through credit notes and in the counterweight exercised or that could be exercised by social security entities and prepaid healthcare companies in the formation of the retail price of outpatient medicines as a result of their purchasing power.

Consequently, under this analysis, no objections from the CNDC have been given to the general structure of the market for medicines that support the opening of behavioral investigations or additional conditions for concentration processes.